Despite clear evidence that Hsp12 - a so-called heat shock or stress protein - helps cells survive life-threatening conditions, how it works was an open question until now. The surprising answer is revealed in the Aug. 27 issue of Molecular Cell, where German researchers explain how they discovered the function of Hsp12, a protective mechanism unlike any previously observed. Unfolded within the cell's aqueous cytosol, Hsp12 folds into helical structures to stabilize the cell membrane.

One way the single-celled model organism S. cerevisiae, brewer's yeast, responds to stress is to increase production of Hsp12 several hundred times. This evidence that Hsp12 must have a protective function, together with its small molecular mass, led to its classification with other heat shock proteins (HSPs). Yet an exhaustive investigation led by Munich-based researchers has revealed that Hsp12 is structurally and functionally different from every other stress protein that has been studied before. The scientists say that Hsp12 defines an entirely new class of stress proteins in which it stands, at least for now, alone.

This is a new concept for protecting cells against stress," says Johannes Buchner, professor of chemistry at the Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM) and a member of the Munich Center for Integrated Protein Science. "This is the most abundant protein in the yeast S. cerevisiae under stress - not only heat, but different kinds of stress - and we found that it does not protect other proteins from unfolding or aggregation as other HSPs do. Instead, it binds to membranes and stabilizes them against rupture and leakiness."

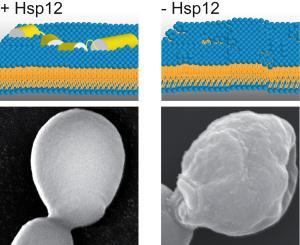

Unlike other stress proteins, Buchner and his collaborators observed, Hsp12 is completely unfolded in its native state. They found that it exists both in solution, in the yeast cell's aqueous cytosol, and in association with the cell's outer wall, the plasma membrane. Its protective mechanism appears to work in the following way: As Hsp12 synthesis increases in response to stress, the higher concentration of the protein brings more of it into contact with the membrane; interacting with the membrane, Hsp12 folds, forming helical structures that become partially embedded in it. The Hsp12 helices bind to specific kinds of lipids, but evidently not in such a way as to change the membrane's composition; instead, these interactions appear to change the way the membrane is organized, enhancing its integrity and stability. The transformation of Hsp12 from its unfolded state in solution to its folded state as a membrane chaperone appears to be completely reversible.

This remarkable mechanism was uncovered step by step through a long and complex series of experiments, most of which involved "wild type" S. cerevisiae and a "knockout" strain of yeast that could not synthesize Hsp12. The interdisciplinary research team brought more than a dozen advanced analytical methods into play, as each discovery along the way raised new questions that had to be answered.

The researchers found that the cellular survival mechanism provided by Hsp12 functioned under several different kinds of assault, including heat shock, oxidative stress, and osmotic stress - a sudden change in the solution surrounding a cell that challenges its ability to regulate the flow of water through the membrane. Results of aging experiments showed a protective function as well. The current paper in Molecular Cell also presents evidence that Hsp12 enhances the health of yeast cells under normal physiological conditions.

Further intriguing questions always grow out of discoveries in yeast, because other eukaryotes - including humans - share so much of this model organism's evolutionary inheritance. How highly conserved and how widely spread is the newly discovered protective mechanism of Hsp12? When did it develop, in what kind of organism? Is it unique to S. cerevisiae? If it exists in other organisms, does it function in a similar way? The Munich-based team used bioinformatic genome searches to extend their investigation in this direction, but without reaching conclusive answers. The researchers did find that the DNA sequences of other fungi code for proteins that could be considered Hsp12 "family members," and they identified one protein in human neurons that may have similar features.

This research was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the CompInt project of the Elitenetzwerk Bayern, as well as by the Excellence Cluster Munich Center for Integrated Protein Science (CIPSM) and the TUM Institute for Advanced Study.

Further Information:

Sylvia Welker, Birgit Rudolph, Elke Frenzel, Franz Hagn, Gerhard Liebisch, Gerd Schmitz, Johannes Scheuring, Andreas Kerth, Alfred Blume, Sevil Weinkauf, Martin Haslbeck, Horst Kessler, Johannes Buchner:

Hsp12 Is an Intrinsically Unstructured Stress Protein that Folds upon Membrane Association and Modulates Membrane Function.

In: Molecular Cell; Volume 39, Issue 4, 507-520, 27 August 2010, DOI 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.001

Source: Technical University of Munich, Germany, TUM

Last update: 02.09.2010

Perma link: https://www.internetchemistry.com/news/2010/sep10/hsp12-provides-a-cellular-survival-mechanism.php

More chemistry: index | chemicals | lab equipment | job vacancies | sitemap

Internetchemistry: home | about | contact | imprint | privacy

© 1996 - 2023 Internetchemistry