|

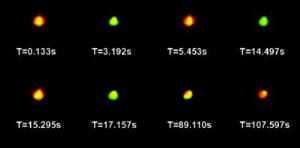

Researchers at Ohio State University have invented fluorescent nano-particles that change color to tag molecules under the microscope. This series of photos shows a particle changing from red to green - and, at the 89-second mark, to yellow - over the course of two minutes.

[Image by Gang Ruan, courtesy of Ohio State University] |

A bottleneck to combating major diseases like cancer is the lack of molecular or cellular-level understanding of biological processes, the engineers explained.

"These new nanoparticles could be a great addition to the arsenal of biomedical engineers who are trying to find the roots of diseases," Ruan said.

"We can tailor these particles to tag particular molecules, and use the colors to track processes that we wouldn't otherwise be able to," he continued. "Also, this work could be groundbreaking for the field of nanotechnology as a whole, because it solves two seemingly irreconcilable problems with using quantum dots."

Quantum dots are pieces of semiconductor that measure only a few nanometers, or billionths of a meter, across. They are not visible to the naked eye, but when light shines on them, they absorb energy and begin to glow. That's what makes them good tags for molecules.

Due to quantum mechanical effects, quantum dots "twinkle" – they blink on and off at random moments. When many dots come together, however, their random blinking is less noticeable. So, large clusters of quantum dots appear to glow with a steady light.

Blinking has been a problem for researchers, because it breaks up the trajectory of a moving particle or tagged molecule that they are trying to follow. Yet, blinking is also beneficial, because when dots come together and the blinking disappears, researchers know for certain that tagged molecules have aggregated.

"Blinking is good and bad," Ruan explained. "But one day we realized that we could use the 'good' and avoid the 'bad' at the same time, by grouping a few quantum dots of different colors together inside a micelle."

A micelle is a nano-sized spherical container, and while micelles are useful for laboratory experiments, they are easily found in household detergents – soap forms micelles that capture oils in water. Ruan created micelles using polymers, with different combinations of red and green quantum dots inside them.

In tests, he confirmed that the micelles appeared to glow steadily. Those stuffed with only red quantum dots glowed red, and those stuffed with green glowed green. But those he stuffed with red and green dots alternated from red to green to yellow.

The color change happens when one or another dot blinks inside the micelle. When a red dot blinks off and the green blinks on, the micelle glows green. When the green blinks off and the red blinks on, the micelle glows red. If both are lit up, the micelle glows yellow.

The yellow color is due to our eyes' perception of light. The process is the same as when a red pixel and green pixel appear close together on a television or computer screen: our eyes see yellow.

Nobody can control when color changes happen inside individual micelles. But because the particles glow continuously, researchers can use them to track tagged molecules continuously. They can also monitor color changes to detect when molecules come together.

Winter and Ruan said that the particles could also be used in fluid mechanics research – specifically, micro-fluidics. Researchers who are developing tiny medical devices with fluid separation channels could use quantum dots to follow the fluid's path.

The same Ohio State research team is also developing magnetic particles to enhance medical imaging of cancer, and it may be possible to combine magnetism with the quantum dot technology for different kinds of imaging. But before the particles would be safe to use in the body, they would have to be made of biocompatible materials. Carbon-based nanomaterials are one possible option.

In the meantime, Winter and Ruan are going to continue developing the color-changing quantum dot particles for studies of cells and molecules under the microscope. They are also going to explore what happens when quantum dots of another color – for instance, blue – are added to the mix.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, an endowment from the William G. Lowrie family to the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and the Center for Emergent Materials at Ohio State.