|

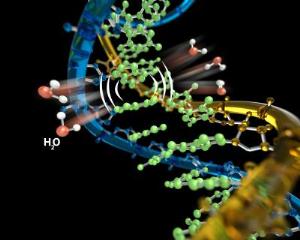

One example of how hydrophobic interactions are critical to biomedical applications can be found in how DNA base pairs on the two strands are drawn together to form a double helix. The basic structure of a DNA molecule is a hydrophilic backbone and a hydrophobic inner region of nitrogenous bases (adenine, guanine, thymine, and cytosine). These molecular hydrophobic forces repel the water between them which drives the bases towards each other.

[Credit: UCSB] |

|

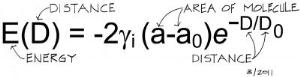

This is Israelachvili’s equation.

[Credit: UCSB] |

"This discovery represents a breakthrough that is a culmination of decades of research," says Professor Jacob Israelachvili. "The equation is intended to be a tool for scientists to begin quantifying and predicting molecular and surface forces between organic substances in water."

Using a light-responsive surfactant – a soap-like molecule related to fats and lipids – the researchers developed an innovative technique to measure or change the forces between layers of the molecule in water by using beams of UV or visible light. The result is a general equation that applies to even more complicated systems, such as cellular membranes or proteins.

"We were fortunate to find the right combination of experimental methods and theory," said Brad Chmelka, UCSB Chemical Engineering professor and co-author of the study. "The keys to our research were using a light-responsive surfactant molecule, a means of measuring these delicate surface forces, and applying knowledge of what to look for."

The highly-sensitive instrument they used to sense these molecular-level hydrophobic forces, called a surface forces apparatus, is a now-standard technique that was originally pioneered by Israelachili and colleagues in the 1970s.

"In basic chemistry, students learn about van der Waal forces – the weak forces that act between all molecules. That theory was developed more than 100 years ago," explains Professor Israelachvili.

"According to the van der Waals theory, however, oil and water shouldn't separate and surfactants shouldn't form membranes, but they do. There has been no proven theory to account for these special hydrophobic interactions. Such behaviors are crucial for life as we know it to exist."

Hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions are central to the disciplines of chemistry, physics, and biology that have fueled modern developments in industries from detergents to pharmaceuticals and new biotechnologies. The new equation is expected to impact applications in water filtration, membrane separations, biomedical research, gene therapy methods, biofuel production, and food chemistry.

Virus and disease propagation in the human body are directly linked to hydrophobic properties on a cellular level. One of the problems related to chemotherapy treatments for cancer is being able to direct a drug specifically to cancer cells, instead of the entire body. Israelachvili and his colleagues foresee their discovery having an impact in biomedical research that attempts to understand and treat diseases.

"Cell membranes are complex and discriminating structures, allowing the transmission of various signals into cells and mediating specific interactions with bacteria and viruses," said Jean Chin, Ph.D., who oversees membrane structure grants at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. "This study, by enhancing our understanding of the role played by hydrophobic forces in membrane dynamics, will expand what we know about membrane structure and function, as well as microbial infection pathways."

"Understanding how water and oil-like substances interact is enormously important for explaining the properties and functions of many biological and engineering materials," says Dr. Robert Wellek, Program Director in the Directorate for Engineering at the National Science Foundation. "The UCSB and USC teams have elegantly combined concepts from synthetic chemistry, photophysics, and chemical engineering to unravel and quantify the elusive hydrophobic interaction. NSF is very pleased that its grantees have been able to contribute important fundamental knowledge in this important area."

Details of the research were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [see below]. Their research was made possible by support from the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Procter & Gamble Company.

"We've known for a long time what we were aiming for. It's a bit like climbing a mountain," said Professor Israelachvili. "The whole thing started at the very bottom. I've been searching for the keys to this interaction for thirty years. We are thrilled with the findings, but it took a lot of steps over carefully chosen paths to get there."

Professor Jacob Israelachvili, Professor Bradley Chmelka, and Stephen Donaldson, Ph.D. student, are with the Department of Chemical Engineering at UCSB. Dr. Israelachvili is a Fellow of the Royal Society of London and member of the U.S. National Academy of Science and the U.S. National Academy of Engineering. Dr. Israelachvili received his Ph.D. in Physics from University of Cambridge and joined UCSB in 1986. He was recently named by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers as one of the "100 Chemical Engineers of the Modern Era" for his achievement and leadership in the field.