The most unambiguous data to date on the elusive 113th atomic element has been obtained by researchers at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Science (RNC).

A chain of six consecutive alpha decays, produced in experiments at the RIKEN Radioisotope Beam Factory (RIBF), conclusively identifies the element through connections to well-known daughter nuclides.

The groundbreaking result, reported in the Journal of Physical Society of Japan [see below], sets the stage for Japan to claim naming rights for the element.

The search for superheavy elements is a difficult and painstaking process. Such elements do not occur in nature and must be produced through experiments involving nuclear reactors or particle accelerators, via processes of nuclear fusion or neutron absorption. Since the first such element was discovered in 1940, the United States, Russia and Germany have competed to synthesize more of them. Elements 93 to 103 were discovered by the Americans, elements 104 to 106 by the Russians and the Americans, elements 107 to 112 by the Germans, and the two most recently named elements, 114 and 116, by cooperative work of the Russians and Americans.

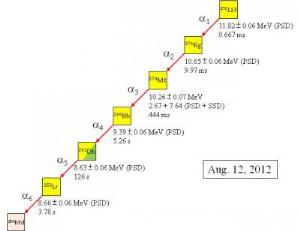

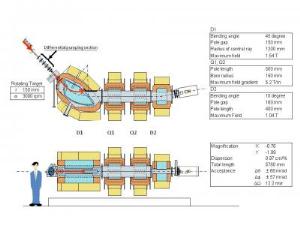

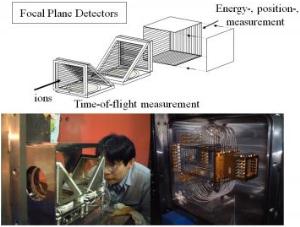

With their latest findings, associate chief scientist Kosuke Morita and his team at the RNC are set follow in these footsteps and make Japan the first country in Asia to name an atomic element. For many years Morita's team has conducted experiments at the RIKEN Linear Accelerator Facility in Wako, near Tokyo, in search of the element, using a custom-built gas-filled recoil ion separator (GARIS) coupled to a position-sensitive semiconductor detector to identify reaction products. On August 12, those experiments bore fruit: zinc ions travelling at 10% the speed of light collided with a thin bismuth layer to produce a very heavy ion followed by a chain of six consecutive alpha decays identified as products of an isotope of the 113th element (Figure 1).

While the team also detected element 113 (systematical name: Ununtrium, today's name: Nihonium) in experiments conducted in 2004 and 2005, earlier results identified only four decay events followed by the spontaneous fission of dubnium-262 (element 105). In addition to spontaneous fission, the isotope dubnium-262 is known to also decay via alpha decay, but this was not observed, and naming rights were not granted since the final products were not well known nuclides at the time. The decay chain detected in the latest experiments, however, takes the alternative alpha decay route, with data indicating that dubnium decayed into lawrencium-258 (element 103) and finally into mendelevium-254 (element 101). The decay of dubnium-262 to lawrencium-258 is well known and provides unambiguous proof that element 113 is the origin of the chain.

Combined with their earlier experimental results, the team's groundbreaking discovery of the six-step alpha decay chain promises to clinch their claim to naming rights for the 113th element.

"For over 9 years, we have been searching for data conclusively identifying element 113, and now that at last we have it, it feels like a great weight has been lifted from our shoulders," Morita said. "I would like to thank all the researchers and staff involved in this momentous result, who persevered with the belief that one day, 113 would be ours. For our next challenge, we look to the uncharted territory of element 119 and beyond."

About RIKEN

RIKEN is Japan's flagship research institute devoted to basic and applied research. Over 2500 papers by RIKEN researchers are published every year in reputable scientific and technical journals, covering topics ranging across a broad spectrum of disciplines including physics, chemistry, biology, medical science and engineering. RIKEN's advanced research environment and strong emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration has earned itself an unparalleled reputation for scientific excellence in Japan and around the world.

About the Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Science

Named after the father of modern physics in Japan, Yoshio Nishina, the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science (RNC) carries on a long tradition of pioneering accelerator science, boasting the world's most powerful facilities for heavy ion physics. Since its inauguration in 2006, these facilities have drawn the attention of nuclear physicists around the globe with their promise to reveal a world of physics that exists only in the hottest stars, and in earliest stages of our universe.

Using its world class facilities, the RNC has set out to tackle two main goals: firstly, to greatly expand our knowledge of the nuclear world into regions of the nuclear chart presently beyond our grasp, and secondly, to apply this knowledge to other fields such as nuclear chemistry, bio and medical science, and materials science. Through international collaborations with researchers around the world, the center is uniquely positioned to succeed in achieving these goals in the years to come.

Further Information:

Kosuke Morita et al.:

New Result in the Production and Decay of an Isotope, 278113, of the 113th Element.

In: Journal of Physical Society of Japan; J. Phys. Soc. Jpn., 81, 103201, (2012), DOI 10.1143/JPSJ.81.103201

Source: RIKEN, Japan

Last update: 29.09.2012

Perma link: https://www.internetchemistry.com/news/2012/sep12/ununtrium-decay.php

More chemistry: index | chemicals | lab equipment | job vacancies | sitemap

Internetchemistry: home | about | contact | imprint | privacy

© 1996 - 2023 Internetchemistry