|

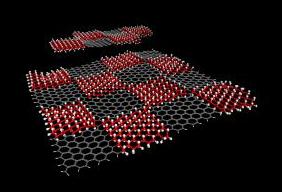

Making a superlattice with patterns of hydrogenated graphene is the first step in making the material suitable for organic chemistry. The process was developed in the Rice University lab of chemist James Tour.

[Credit: Tour Lab/Rice University] |

|

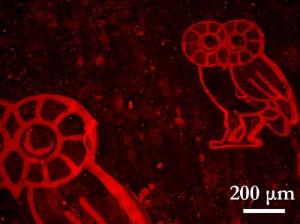

Researchers at Rice printed owls, the university's mascot, in hydrogen atoms on a graphene substrate, turning it into a graphane superlattice suitable for organic chemistry. As proof, they "lit up" the owls by coating them with a fluorophore and viewing them through fluorescence quenching microscopy. Graphene quenches fluorescence, but the molecules shine brightly when attached to the superlattice.

[Credit: Zhengzong Sun/Rice University] |

Until now there was no way to attach molecules to the basal plane of a sheet of graphene, said Tour, Rice's T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and of computer science. "They would mostly go to the edges, not the interior," he said. "But with this two-step technique, we can hydrogenate graphene to make a particular pattern and then attach molecules to where those hydrogens were.

"This is useful to make, for example, chemical sensors in which you want peptides, DNA nucleotides or saccharides projected upward in discrete places along a device. The reactivity at those sites is very fast relative to placing molecules just at the edges. Now we get to choose where they go."

The first step in the process involved creating a lithographic pattern to induce the attachment of hydrogen atoms to specific domains of graphene's honeycomb matrix; this restructure turned it into a two-dimensional, semiconducting superlattice called graphane. The hydrogen atoms were generated by a hot filament using an approach developed by Robert Hauge, a distinguished faculty fellow in chemistry at Rice and co-author of the paper.

The lab showed its ability to dot graphene with finely wrought graphane islands when it dropped microscopic text and an image of Rice's classic Owl mascot, about three times the width of a human hair, onto a tiny sheet and then spin-coated it with a fluorophore. Graphene naturally quenches fluorescent molecules, but graphane does not, so the Owl literally lit up when viewed with a new technique called fluorescence quenching microscopy (FQM).

FQM allowed the researchers to see patterns with a resolution as small as one micron, the limit of conventional lithography available to them. Finer patterning is possible with the right equipment, they reasoned.

In the next step, the lab exposed the material to diazonium salts that spontaneously attacked the islands' carbon-hydrogen bonds. The salts had the interesting effect of eliminating the hydrogen atoms, leaving a structure of carbon-carbon sp3 bonds that are more amenable to further functionalization with other organics.

"What we do with this paper is go from the graphene-graphane superlattice to a hybrid, a more complicated superlattice," said Sun, who recently earned his doctorate at Rice. "We want to make functional changes to materials where we can control the position, the bond types, the functional groups and the concentrations.

"In the future - and it might be years - you should be able to make a device with one kind of functional growth in one area and another functional growth in another area. They will work differently but still be part of one compact, cheap device," he said. "In the beginning, there was very little organic chemistry you could do with graphene. Now we can do almost all of it. This opens up a lot of possibilities."

The paper's co-authors are graduate students Daniela Marcano, Gedeng Ruan and Zheng Yan, former graduate student Jun Yao, postdoctoral researcher Yu Zhu and visiting student Chenguang Zhang, all of Rice.

The work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Sandia National Laboratory, the Nanoscale Science and Engineering Initiative of the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research MURI graphene program.